Why hazard pay didn’t last through COVID-19

And how we have to bring it back for the next pandemic

Written by @AlexC_Journals, a journalist who wishes safety spring chairs on cars went mainstream.

5 minute read

THE GUIDING QUESTION

Where did hazard pay come from, and when did it become a mainstream idea? More importantly, what will it take for it to exist—for everyone—by default?

THE TEASER

COVID has made for hazardous working conditions, but hazard pay—benefits for working in dangerous conditions—barely made a blip as a U.S. policy response.

But the Coachella city council just adopted an emergency mandatory ordinance for hazard pay for agricultural workers—the first of its kind.

We’re taking a deep dive into the context of hazard pay, how it became a thing, and how it (mostly) disappeared just as fast in 2020.

THE DEEP DIVE

Chances are that until COVID, you never thought about hazard pay.

Why? Because it didn’t apply to you. Unless you were already involved in traditionally dangerous work (think chemical worker, miner, etc.), it probably never crossed your mind.

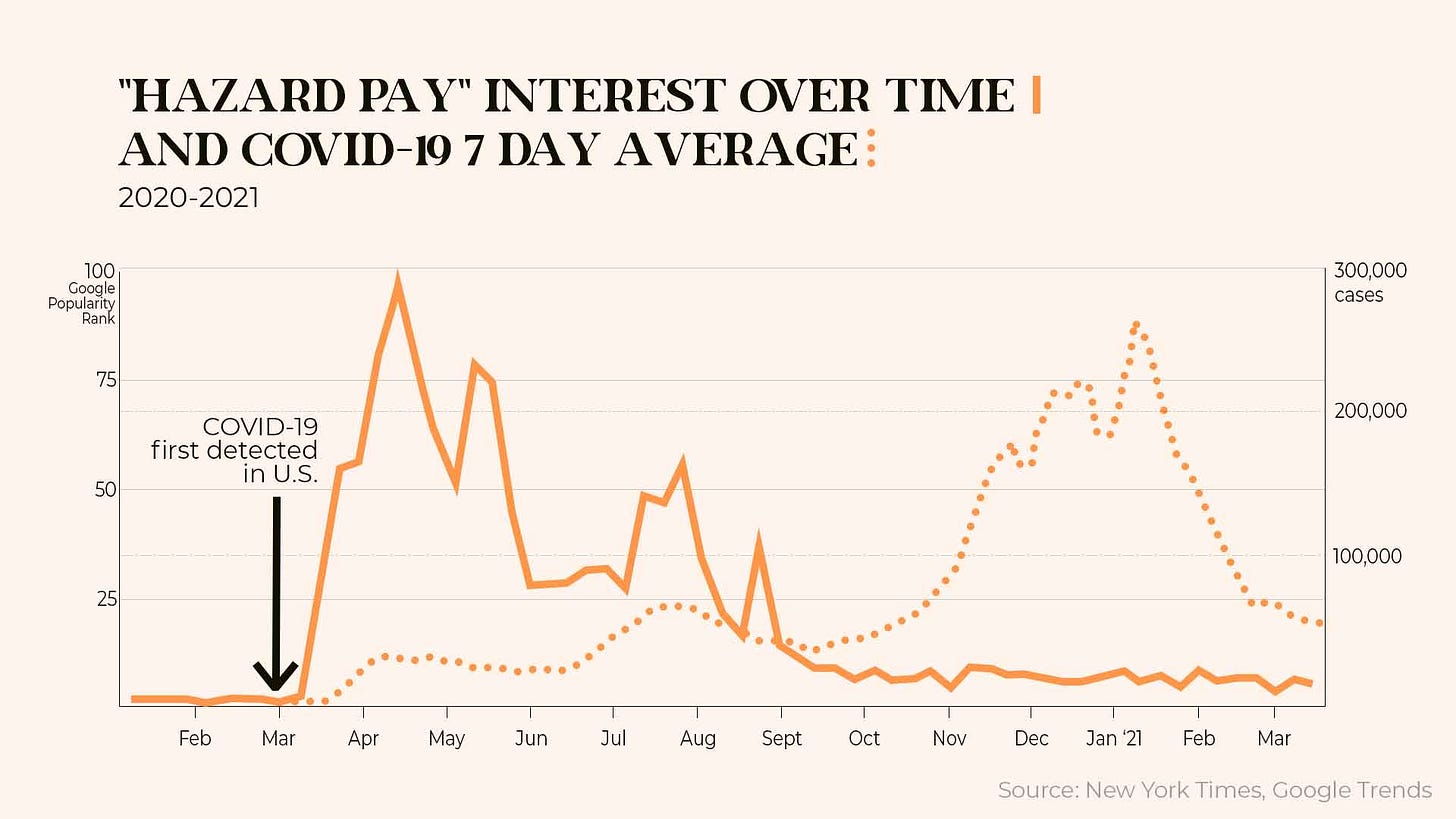

In fact, you can see exactly how much it never crossed our minds in this chart.

What you’re looking at is the Google Trends data for “hazard pay.” For 10 years, there’s barely a blip. But zoom into March 2020—exactly when the first cases of COVID get reported—and suddenly interest is off the charts.

Covid happened.

And instead of a small proportion of the country, half the population had jobs that were hazardous. Anyone who took care of the elderly, worked at a grocery store, worked retail, drove an Uber… basically anyone in contact with multiple humans was a walking hazard sign.

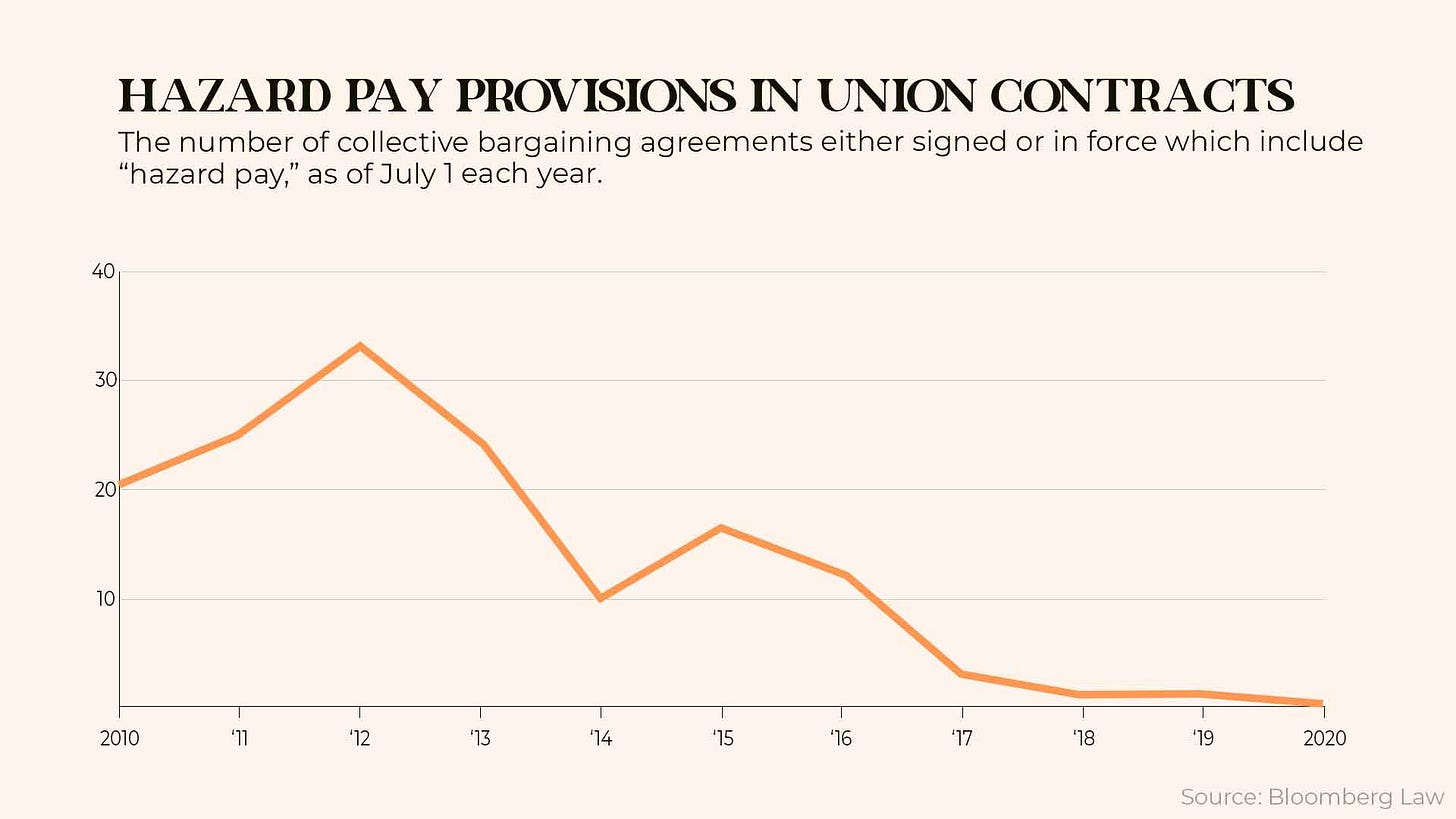

But hazard pay isn’t federally regulated. It’s not built into any state laws. There isn’t any enforcement agency for it. Nada. Sure, technically the Fair Labor Standards Act does mention hazard pay, but it’s not required and it doesn’t provide a standardized rate. And only one union contract negotiated in the past year even mentions it, according to Bloomberg Law.

Even under the crazy circumstances of this pandemic, the government hasn’t seemed to rise to the occasion to pass hazard pay legislation.

Hazard pay is in political and legal limbo.

It kind of always has been.

From what little contextual and historical research we could find, and we mean we found very little, hazard pay has bloomed out of a century of, well to put it candidly, people dying on the job.

Some (brief but important) historical context.

Workers’ protections generally started trending with the safety of factory workers coming into question in the late 19th century. Little by little came protections, though extremely specific based on job and industry, for workers through various commissions and councils—like with the Interstate Commerce Commission that protected railroads in 1887, and the Federal Radiation Council in 1959 that protected against radiation hazards.

For the record, we’re obviously glossing over a ton here—like the development of workers’ compensation in 1908, the creation of the Bureau of Labor Standards in 1934, and the Johnson era of patchwork federal laws to protect workers—but the TLDR of it is this:

It wasn’t until the 1970 Occupational Safety and Health Act under Nixon that the OSHA standards we know today crystalized to cover multiple workers' rights industries—and it had some teeth, mandating hefty fines on unsafe conditions.

But again, these were laws made for people already working in traditionally hazardous fields. It wasn’t designed to expand to industries that are only hazardous sometimes, i.e. during a pandemic.

What’s developed since...

Most of the impetus to protect workers at this point is delegated to unions. They’re the ones who write hazard pay into your contract.

But here’s the catch: this is assuming you are a worker who is a part of a union with any degree of bargaining power—and that is a huge if.

According to the Economic Policy Institute, only 12% of essential workers are part of a union, and only 11% of nonessential workers are part of a union. And the unfortunate truth is, a lot of unions, even if they do exist, are a kind of paper tiger without any power to bargain anything for anyone.

So putting two and two together makes for a bleak outlook.

If hazard pay isn’t regulated by the federal government (which it’s not)...

And not a ton of people are part of unions who can bargain on their behalf (which they’re not)...

And companies have so far proven that they don’t often include hazard pay simply out of their own goodwill (which they don’t)...

What is the American worker supposed to do? Not just for this pandemic, but for the next one?

States are on their own.

Various cities are taking it upon themselves to create mandates for hazard pay for workers in traditionally non-hazardous roles, like essential grocery and food retail workers in California.

But what this comes down to is two things:

In the absence of federal or statewide rules, unions need more people and more power.

Unions are going to be the bargaining arm for workers who have to keep the economy running and who arguably deserve hazard pay for working in unusually unsafe conditions.The government has to reconsider the definition of a hazard.

Hazards, like pandemics, may be cyclical, and while some industries would normally be able to say whether a hazard is controlled or nonexistent, workers have to be able to raise claims for when hazard pay should kick in.

For example, healthcare workers would normally be given protective equipment in the normal course of business. But since that equipment was widely unavailable during the pandemic, as we saw with PPE shortages, there is an argument that healthcare workers deserve hazard pay—and that’s just one industry to consider.

WHY THIS STORY IS WORTH IT

This isn’t the only pandemic the world has seen, and it likely won’t be the last. Workers’ rights have slowly become more of a priority over the last century, and this is the first and only time hazard pay has entered the public eye as a viable option for workers. Regardless of your opinion of hazard pay, this story will play a role in future legislation and ultimately, a role in future political administrations as it moves from city law, to state, to federal.

PEOPLE WORTH INTERVIEWING

Paige Smith and Fatima Hussein from Bloomberg Law. These reporters dove into the legal history and opposing arguments regarding hazard pay.

Molly Kinder and Laura Stateler from the Brookings Institute. Their research, and the institute overall, have done extensive research on hazard pay and the experience of essential workers during the pandemic.

WHAT WE DON’T HAVE ANSWERS TO

It’s hard to speculate on the future of hazard pay. Speaking to policy and legal experts, like those at Bloomberg and Brookings, would give us a better sense of how hazard pay legislation in the future will take shape, if at all.

WE’LL SEE YOU ON THE WIRE

Want another pitch in time for your next meeting?

Know someone who’d love this pitch?

Publishing this story? See a correction? Got a tip? Tell us and we’ll publish it!

ADDITIONAL SOURCES

Nation's first mandatory farmworker hazard pay gains approval

Hazard Pay Plans Poised to Outlast Virus With Bipartisan Push