A pitch by @AlexC_Journals, a journalist who thinks bunnies make great boxers.

A 6 minute read

A SPECIAL NOTE

This week, not only do we have a great pitch for you, but we turned our interviews into a podcast! You can hear our research coming directly from the source’s mouth, and you’re welcome to take any part of the podcast for your own story—no strings attached.

THE GUIDING QUESTION

Who stays behind when a website “dies?”

THE TEASER

You’ve heard their names.

Runescape. Neopets. Toontown. LiveJournal. Myspace. Gaia Online.

Logic might dictate that these sites should be dead. They can’t possibly be alive. Right?

Wrong.

We spoke to the people who are still on these sites 2 decades later and asked cyber psychologists to help us understand why.

The answer? A mix of nostalgia for bonding with a community, a desire to feel like a competent expert in something you value, and a need for consistency and control in a world that feels on fire.

These sites likely won’t be managed forever—everything expires on the internet—but a look into the minds of these evangelists proves that they’ll hold on for as long as they possibly can.

THE DEEP DIVE

The Inception of giants

You can’t start this story without realizing the sheer gargantuan size of these sites, both in terms of the number of users and time committed. They weren’t just casually popular. They were generation-defining.

Let’s take a look at 2 examples (although there are easily dozens, if not hundreds)

Neopets, circa 1999

Simply put, Neopets was a pet collecting website. Kind of like a complicated economy of colorful internet Tamagotchi.

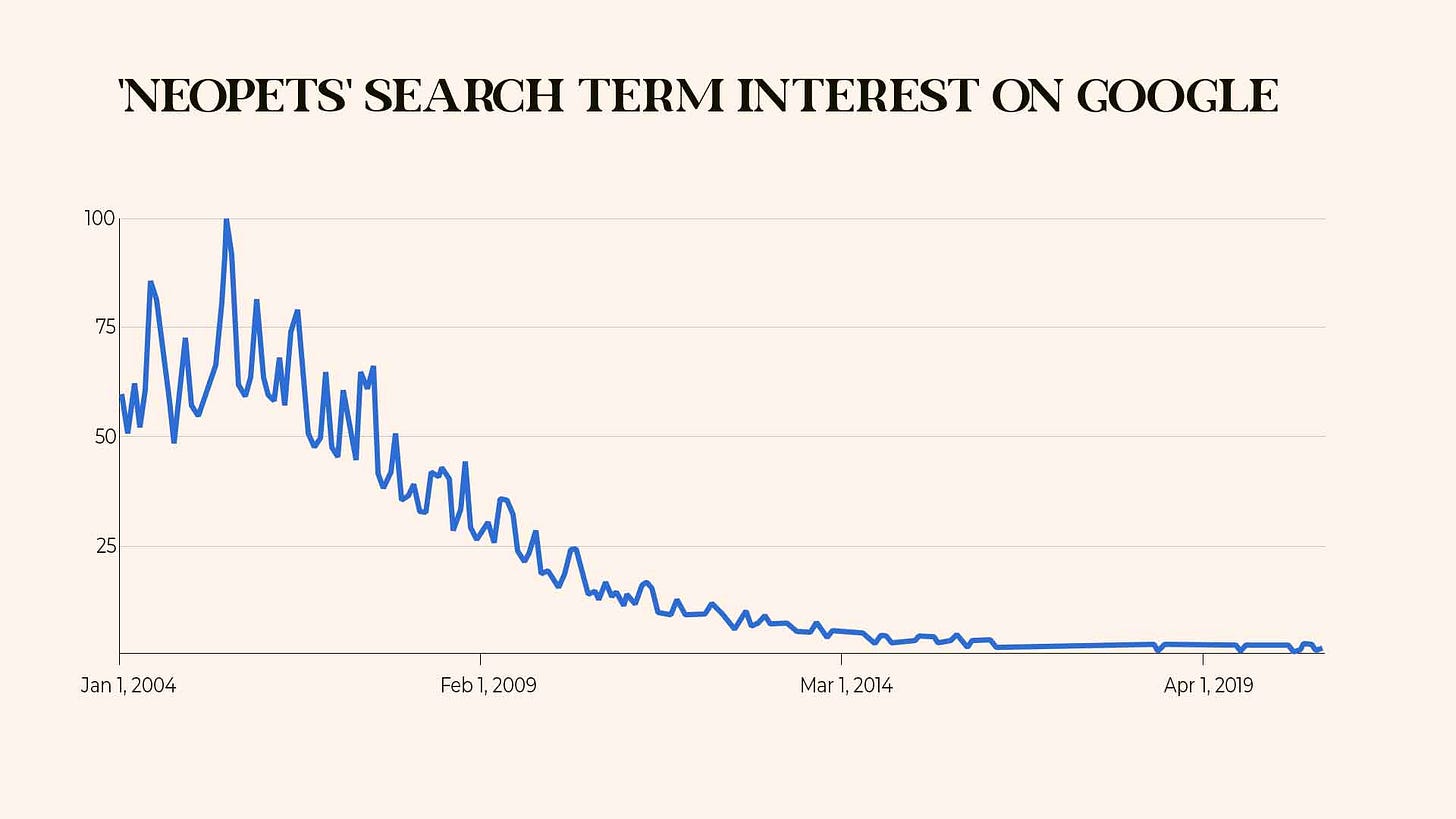

Interest peaked in the early 2000s, at which point it had 2.2 billion page views a month, with 25 million global members according to Wired. During November 2005, 3.4 million unique users signed on, with users staying on the site for an average of three hours and 45 minutes a month, according to Nielsen//Netratings.

But like all things, interest faded after the company was bought, sold, bought and sold again, generally mismanaged, and broke—a lot. Naturally, this sent people away in droves.

But even with a site that looks like it came out of a 2000’s time capsule, JumpStart CEO Jim Czulewicz estimates Neopets still has around 100,000 daily active users and 1.5 million monthly active players. There’s even enough interest that the brand is getting an animated TV series in fall 2021.

To understand the appeal from the perspective of an individual, we interviewed Jaye, one of the players who’s been active on the site and forums for nearly 20 years. And, to understand the appeal on a broader scale, we interviewed 2 cyber psychologists, who focus on the intersection of human psychology and the internet.

Runescape, circa 2001, a.k.a. The exception that proves the rule

Neopets might exemplify a more expected and common website lifecycle, but Runescape—an online fantasy role-playing game—is worth paying special attention to, specifically because it’s the exception to the rule.

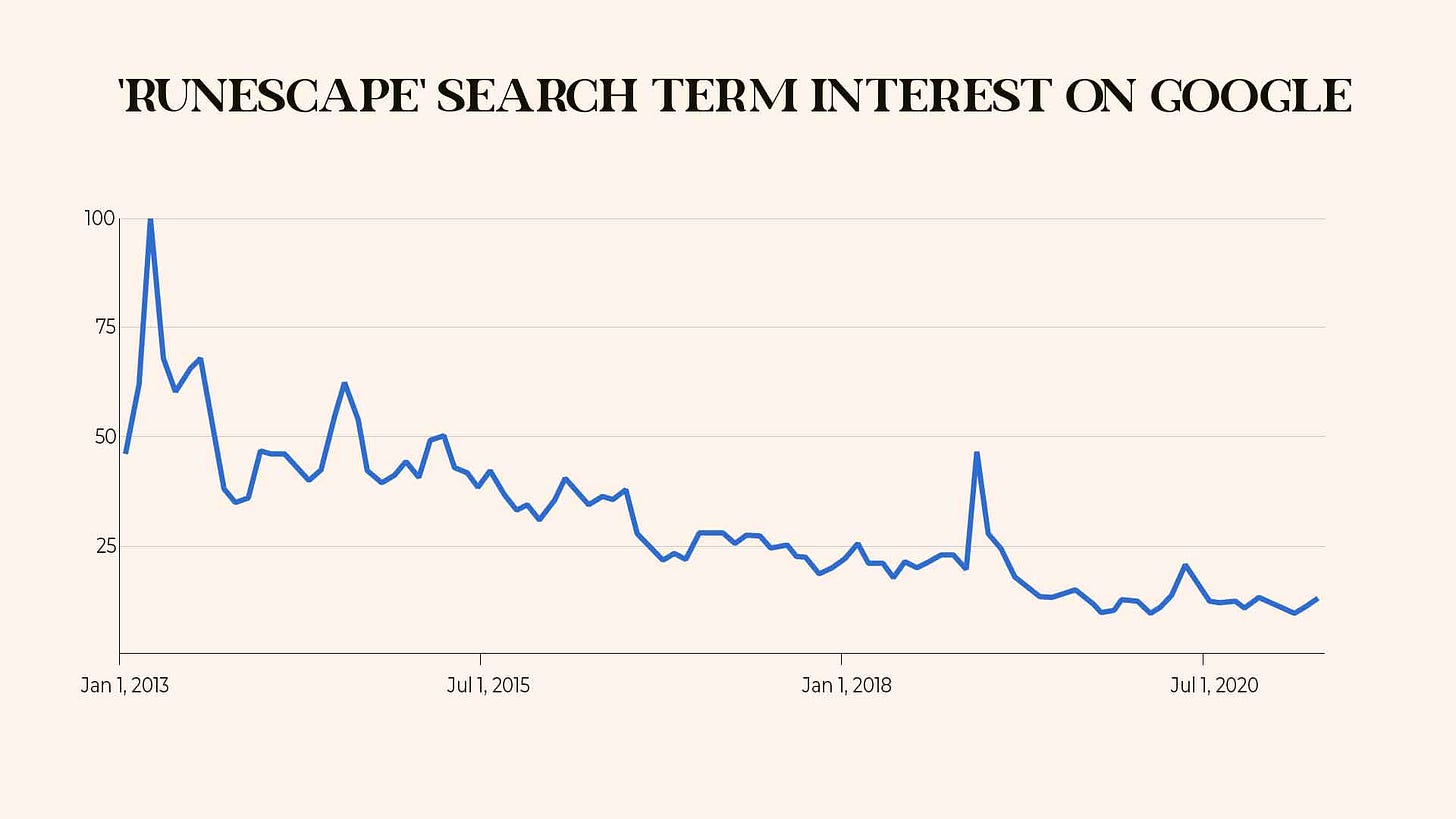

You’d normally expect a site with interest like this to have a declining user base.

But instead, we were shocked to find the exact opposite—users, specifically paid users, have increased, hitting a peak of active users during the pandemic (something you can hear our interviewees speak extensively on during the podcast).

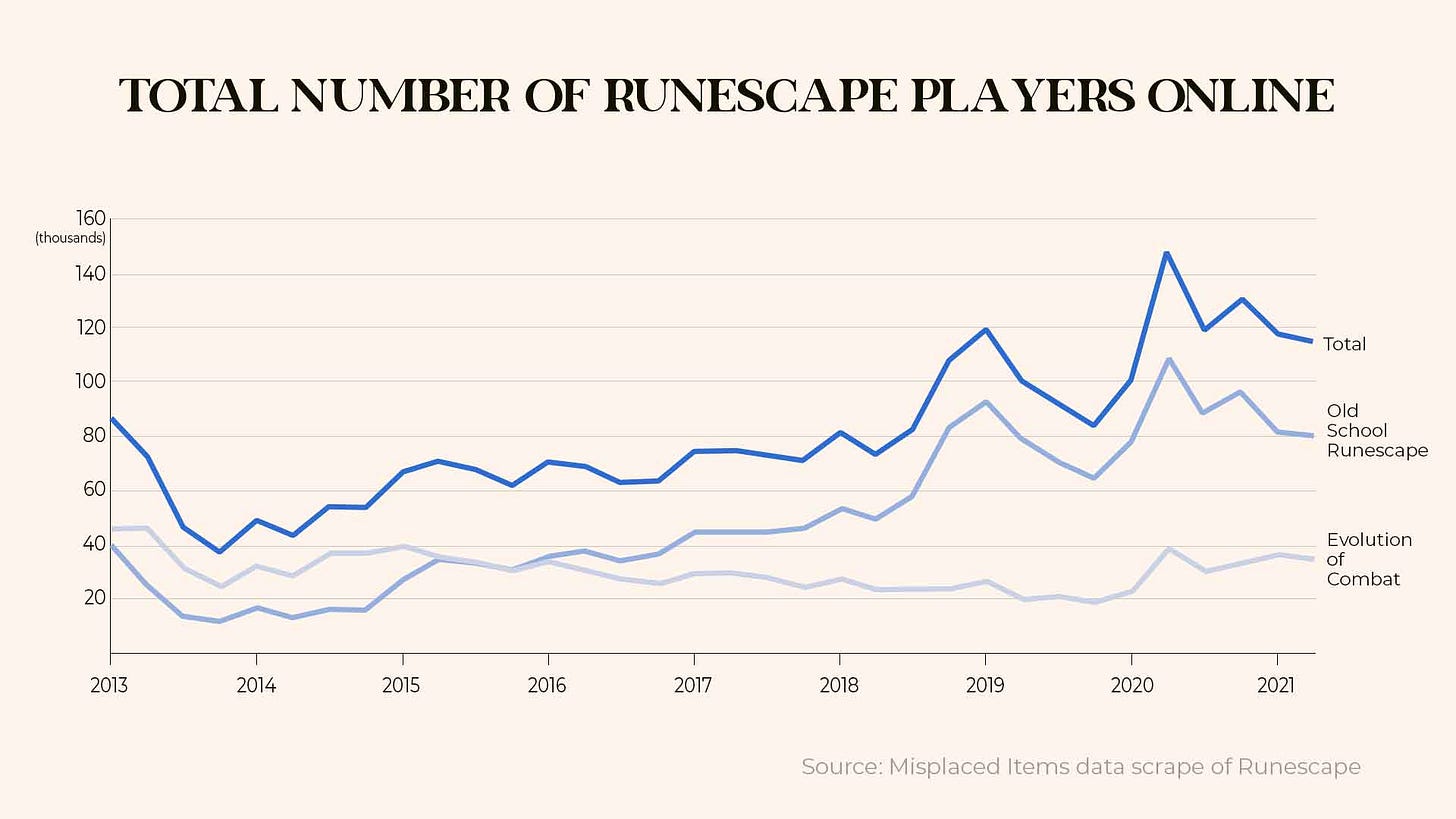

Runescape split in 2013, specifically offering a new version of the game, called Runescape 3, and offering “Old School Runescape” (OSRS). OSRS was a hit like it had always been, performing as an economic cash cow with 1.1 million paid subscribers in 2019, and the mobile version hitting 8 million installs as of January 2020.

The important thing to note here though is that the psychology of these players, particularly because they’ve been active for so long mirrors that of other old websites almost exactly (you can hear this in our interview with Runescape player Sage on the podcast).

Those parallels are worth paying attention to for one key reason—especially if you love playing internet archaeologist:

They tell us what an internet life cycle looks like, and more importantly, they suggest we’ll see the life cycle of Neopets play out time and again in the future.

Here’s how the life cycle of a website seems to work

As a thought experiment, we tried to rub our crystal ball and see if we could align any trends of these websites, both through data and interviews, with currently popular sites.

After all, there seems to be a behavioral trend behind a good portion of websites (Runescape of course being one commercial success and exception):

There is an innovative idea

It’s hugely popular

It sells for big dollars

Then it sells for medium dollars, often when the platform finds difficulty in monetizing their audience or there is a massive technical change (like the death of flash or smartphones going mainstream) that makes it challenging to maintain

It sells for whatever it can

It still exists online, thanks to its long term evangelists, but it’s largely forgotten

So what is the next site that will enter the “old age of the internet”—where enough people share the same psychological characteristics that keep the website functioning and technically active, but it otherwise is a shrunken down version of its former popularity?

The most obvious case: Tumblr, circa 2007

Tumblr, like other sites, was a pretty immediate success, meaning it was bought out by Yahoo! Inc. in 2013 for $1.1 billion.

But the porn ban might have been the first nail in the coffin since, as of July 2019, the platform had surpassed 472 million registered accounts, whereas in the same period it had only 376 million unique visitors—a sharp 20% drop since December 2018.

Consequently, the parent company of WordPress, Automattic, bought Tumblr for less than $3 million in August 2019.

But death be damned, I’m not leaving

Even though we might be able to pinpoint which sites might be on the decline, it’s still crucial to understand that there is a reason they won’t die. And that’s because people won’t let them.

Through half a dozen interviews, we found clear consistencies in user behavior, and much of it was extremely heartwarming.

Nostalgia and consistency, particularly when things felt out of control during the pandemic. This was particularly important as we found people would take long breaks but always returned because they wanted a sense of cozy familiarity.

As old as these sites were, the content was always updated, appealing to a sense of discovery and accomplishment so they’d want to regularly check-in.

An emotional bond with other users who understood the love, and often struggle, of being on these sites for extended periods of time. We often found that users would even engage in meta ways—talking about the site somewhere else entirely offsite like Reddit, Snapchat, or Facebook with the community they exclusively grew onsite.

You can listen more in-depth and hear what drove them to stay on for so long on our podcast.

WHY THIS STORY IS WORTH IT

You may not expect it, but nostalgia is an economic force. And through virtue of simple time, it will be an economic force that keeps countless brands alive, long past their expected expiration date.

As the internet matures, these ghosts of websites are bound to have their cult fans littered all over the corners of the web, putting in money and time into something that never lost its charm.

PEOPLE WORTH INTERVIEWING

We found countless sources mainly through Reddit forums and you can hear our interviews in the podcast!

But we also recommend chatting with cyberpsychology experts, who really helped us understand which behaviors were common among many people and not just the folks we interviewed.

We chatted with Scott Debb, associate professor of psychology at Norfolk State University and the program coordinator for the Master of Science program in cyberpsychology, and Dave Harley, a principal lecturer from Brighton University and an expert on cyberpsychology.

They were phenomenal experts, but we also recommend:

Naomi Clark, faculty at the NYU Game Center with a long history of being part of those game communities and a connoisseur of early online culture.

Amy Jo Kim, a game designer who focuses specifically on community design and has worked as a consultant on many MMO games. She thinks about the technical, social, cultural, and narrative aspects of games altogether, giving her a uniquely comprehensive perspective.

Any writers of the book Cyberpsychology as Everyday Digital Experience across the Lifespan

WHAT WE DON’T HAVE ANSWERS TO

We mostly spoke with people who played games online, but a lot of this psychology applies to people who were active on forum websites too like Gaia Online. We would highly recommend chatting with folks who are still active on social sites in order to differentiate them from people who are attracted to playing games online.

Another angle could be—what happens to the expected life cycle of social media sites like Facebook? Is there a certain point where so many people end up on it that it can actually never die? Or will everything, Facebook included, inevitably end up in an internet graveyard?

WE’LL SEE YOU ON THE WIRE

Want another pitch in time for your next meeting?

Know someone who’d love this pitch?

Publishing this story? See a correction? Got a tip? Tell us and we’ll publish it!

ADDITIONAL SOURCES

Video Games as Time Machines: Video Game Nostalgia and the Success of Retro Gaming

Meet the people who still use Myspace: 'It's given me so much joy'

AIM, Club Penguin, Myspace, and 10 popular social networks in 2010 - Business Insider

Disclaimer: We love these ideas, but they are not fully fleshed-out stories. These are pitches intended as a starting point for other journalists to investigate further and as such, require more interviewing, analysis, and fact-checking before they can be considered full articles. If you’d like to learn more about our pitch process and what goes into Case By Case (and what doesn’t), please check out our FAQ.

TRANSCRIPT

Alex: When I was 13, I wasn’t allowed to play computer games. So instead I would tell my mom I’d be at the library after school. Which, I thought was pretty clever. Because if I could bolt out the classroom door right at the sound of the bell, I could make it to the one library computer that had internet access before other students swarmed. And for 35 minutes, before the computer automatically shut down, I would play this online adventure game called RuneScape. My friends would play Neopets. Check-in on LiveJournal. Or Myspace. Or Gaia Online. All of these sites that defined our generation.

Some joined in because it was the cool thing to do.

And some of them… never left.

This is the story of why they chose to stay––why some people engaged with those iconic sites for 10, 15, 20 years, long after those sites faded from the mainstream and long after their friends hopped onto the next big thing. We're here to explore the psychology behind their choices... and what we discovered is something far more relatable and uniquely human than you might expect.

Welcome to Case By Case, a resource for journalists looking for their next great story. I’m Alex Cardinale, producing this content with my colleague Kate Redding.

Jaye: I have been on Neopets since I was 8 years old. I am now 25, almost 26. I have over the years had five different accounts and I still have access to all of them, which, if you know much about Neopets, that is a miracle.

Alex: From 8 to 26. That’s nearly 20 years. For most of their life, Jaye was a part of the loud, crayola-colored, online world of Neopets. It’s no understatement to say that after so long, it became a cornerstone of Jaye’s life through their most formative years.

Jaye: I am a grad student; I have clinical placement research, I'm teaching and I'm also taking classes, so I'm pretty busy. But still somehow [00:01:40] make time for Neopets, of course. There's definitely a sense of comfort with the consistency. [00:18:40] Whether it's just the actual layout, the style, the look of the website. I think it makes sense for me. I like routine. I like sameness. So I think it kind of makes sense that it's stuck with it for that long.

Alex: In case you don’t know what Neopets is, the simple way to describe it is a virtual pet community. You collect pets. There are online forums. There were little flash games to play. And in the early 2000s, it had 2.2 billion page views a month, with 25 million global members according to Wired. But something about this site was particularly sticky… what was bubbling underneath the surface of these cartoony characters? What made it better than sticking a Tamagotchi online?

Jaye: Neopets, oof, one sentence. Okay. Neopets is a virtual pet site that is based on a world called Neopia and they have a functional economy. They have a stock market, they have a battle dome. You can win items. You can battle NPCs. You can also battle other people's pets. There's a lot of gambling involved. There's a lot of games. There are art contests. Wow, this is more than one sentence. I'm sorry.

When I was younger, I could not have been more excited to finish my homework and get to go on Neopets. Even if it was just for like 30 minutes a day, I don’t know. My parents, they never really had to limit my screen time, but I was always just so excited to come home and do my homework and then I got to go on Neopets.

Alex: As it evolved, Neopets got more complex. It functioned like an entire ecosystem, mixing games and forums and economics all in one—and it stayed pretty popular.

But years came and went, and it was bought and sold from company to company, and they didn’t handle transitions well.

Over the years it got glitchy and the site would lag. Flash eventually died, and along with it, all the Neopets games that depended on that software, so a huge portion of the community moved on with their lives, playing newer, oftentimes simply prettier games. Even evangelists like Jaye would end up leaving… but some of them always managed to find their way back.

Jaye: No, I definitely took some breaks... early high school, mid-high school took a little bit of a break, but still was on it every now and then, just wasn't a daily thing anymore.

Yeah, I would definitely come back every now and then check-in and check on my pets. See if I had any Neomail. Just say hi, basically.

Oh man, when I first came back and checked my side accounts, I was pretty upset. I was like, wow, I have no Neofriends online. Also. It shows you when your friends are online and the message that it says when there's no friends online, it says none of your Neofriends are online. You must be lonely.

So I was like, “I am!” And I think it even has a little sad face emoji next to it too.

Alex: At this point in the story, I have to stop myself. Because this entire time, I was assuming that the people who played games and engaged with online communities like this were just, kind of consistent about it. That they were just always there. At least when I think about it, if I were to take a break from something, for years, it’s a huge hurdle to not just come back… but to start being consistent again. Where was the trigger? And why was this space something someone like Jaye came back to?

Jaye: Yeah, it definitely was pretty dead. I think what kept me coming back—a few factors. I like collecting things, I always have. And I had started—when I was in middle school, I had started a gallery on my account of Petpets, which, those are pets that you can give to your Neopet.

Some days I’d play games—I mean, they just murdered Flash, so there’s not really any games to play anymore. But up until late January, I'd play the flash games just for fun. But definitely if I had time, I could spend up to like three, four hours at a time either chatting on the Neoboards, playing games looking at all the expensive Petpets that I still need to buy.

Alex: Those answers make sense, right? Nostalgia and natural interest. Neopets as a game and community naturally appealed to something Jaye already enjoyed, and it left an imprint on her from when she was young. Everything from the characters, to color, to soundscaping was familiar. Cozy.

But then... 2020.

2020 wasn’t cozy. 2020 was the biggest emotional trigger many of us experienced basically ever.

Jaye: Yeah, I definitely came back because of quarantine and Neopets really became an escape for me during quarantine, I would spend, I don't even know how many hours during winter break, during quarantine, I would spend because there's, COVID, couldn't go out of the house. It was, like upstate New York. It was freezing. There was three feet of snow. Couldn't go out of the house. I was just sitting on Neopets all day.

You know, being completely overwhelmed by what was happening in the news and the media. I enjoy playing video games and stuff like that, but I wouldn't consider myself like a gamer.

But I just needed some sort of hobby that I could do in the house. So I just, you know, just kept at it.

Alex: Now that is an interesting comment. Familiarity itself wasn’t enough to bring someone like Jaye back to playing these games, and engagement always waxed and waned—in fact, a lot of people we interviewed said that they’d just leave these games playing in the background while they would work or study or do whatever online.

But when you put those two things together, the need for consistency and a feeling of familiarity, they become greater than the sum of their parts.

That snowball of an emotion lives in a unique space. It lives among a community that supports the achievements you’re working towards, a community striving for those same achievements.

That feedback loop gets you this audience of superfans, who come back, without fail, regardless of what life busies them with... superfans who are, in fact, such evangelists, that they still engage with a site that breaks half the time and leaves them feeling frustrated in how it’s updated or mismanaged.

Jaye: I think right now, my first initial reaction when I log on is a little bit of disappointment because they changed the layout of the main page and it just doesn't look like Neopets anymore. But then as soon as I click to a page that hasn't been converted yet, I'm like, okay, there it is.

And it's like, it's nice. It's… it feels very nostalgic. I enjoy it. It's like coming back to it. I mean, I'm 25. I've been on Neopets for 17 years. So that's over two thirds of my life, I would say...

Alex: Disappointed is an incredibly interesting choice of phrase, right? It means that the site can leave a bad taste in someone’s mouth, but something about their psychology and associations still overcome that. Just think about the time and investment it takes for someone to build enough of a relationship with a site for that to happen.

One of the ways people made those investments doesn’t have to do with the site at all. We found that many people enjoyed these sites like Neopets offsite, somewhere like Reddit. It’s an entirely meta experience.

Jaye: During quarantine, I joined the Neopets subreddit, and that’s really when I started feeling like part of the community. I just found it one day—I think it was just out of curiosity, really out of curiosity, that I found the Neopets subreddit. I realized the site was still alive and well and realized that there were a lot of people my age. I always—obviously I looked at it as, like, a little kid site. I think that's what it was, you know, kind of intended for it, what a lot of people think.

But then I realized there were a lot of people, like mid-twenties… like twenties, thirties, even forties and older; grandparents playing Neopets. So it was pretty cool to, to find that. It felt like it was like this whole little, like, hidden underground community that I found in the subreddit.

Alex: Offsite forums became this indirect way people could feel involved with the community, even if the site itself seemed to be falling apart like when people would get locked out of their own accounts and support staff wouldn’t respond to requests for help.

Over time, people found ways to affirm the identities they developed on these sites. And feeling that their identity was affirmed became an incredibly attractive value—something that people came back for on a regular basis. Over years, it was sort of like checking in over your shoulder, to make sure your friends were right behind you, that they were still there, and that you weren’t alone when it felt like the world was on fire. Because at least if the world was on fire… a little part of your world wasn’t.

At least, that was my guess. So I checked in with a couple cyber psychologists to see if we were on the right track.

Debb: It provides a sense of security. You're not alone in the world. You're not isolated. You know, you may be introverted in nine out of 10 places, you know, environments that you're in in your life, but that one place where you feel comfortable, you express yourself. And cyberspace is a great, great media, medium for being able to find that niche.

Alex: Enter Dr. Scott Debb, associate professor of psychology at Norfolk state university, and the program coordinator for the master of science program in cyber psychology. Which, until researching this story, I did not know even was a field of study.

Cyberpsychology is the intersection between behavior and technology. We couldn’t have asked for a more perfect field of experts to answer our burning question: why do people stay on these sites? Especially because, don’t you think these sites would be dead by now? Don’t we expect sites like these to… well… expire?

Debb: I think there’s an expectation that there’s just an inherent expiration date with a lot of things, and if you think of for example, games, gaming—games come out with new versions of themselves, like especially the sports games, there's a new version. There's an expected new version every year.

In my household, we have NHL 21, but we also had NHL 20 and 19 and 18 and 17. And if I go back far enough to when I was a teenager, I had NHL 95 and Sega Genesis.

There's an expectation that there's just going to be something inherently different, but in, ideally, a better way. And so, I think, because of this, just the “human being-ness” being what it is, we’ve learned, like I said, over the last decade or two at least, that things are disposable and there is an expiration date. We don’t expect—holding on to a computer for ten years, it would be unheard of.

Alex: Of course- that makes sense, right? Most versions of the things we interact with have a built in expiration date. Phones. Computers. Your car. Your PlayStation. Why would a website be any different? Logic seems to dictate that technology trains us to want new things. Updated things. So why do we have this diehard commitment to these… digital anachronisms? Where’s the appeal, especially in a place where it seems most people left a long time ago?

Debb: So one of the theories, psychological theories, that I think applies to the question of why people persist with playing certain games or exist, persist with certain communities that are kind of well-established and perhaps past their prime on some level—it’s a theory called the self-determination theory.

So self-determination theory in a nutshell says that what—the things that are essential to motivating people, to human motivation, is autonomy, competence and relatedness, with autonomy being, you know, feeling that… someone feeling as though they can operate independently, that they have choice and agency.

Then competence is obviously, you know, just kind of what it sounds like; it's feeling as though you know what you're doing, that you have a sense of mastery over something, that you're good at something.

And so the last area is relatedness. And that's this basic idea of just being connected with, with people, belonging. The need to belong is a tremendously important factor when it comes to human motivation.

And collectively, if you put these pieces together, what you find is that these, existing, you know, long-term, longstanding communities online communities, gaming communities, social media communities. They combined all these things in one—essentially what happens is that it creates a sense of nostalgia and that nostalgia, again, there's a social component, there's an emotional component. And it really drives people.

Alex: Autonomy, competence, and relatedness. When you put it like that, you start to see that every site that has managed to hang on for so long offers something along those lines. The freedom to make choices, the opportunity to feel skilled in those choices, and the space to feel like those choices are valued by a community. That is the foundation for consistent love… that is a key component of nostalgia.

Debb: And just, just to define nostalgia for a moment; we can probably just boil it down. In emotional experience, it's primarily positive. It has a social component to it. There's an emotional component to it. And it's something from the past. And you combine all those things in this sense of nostalgia. It exists in your mind, right? It's not… it's not tangible. But it impacts you in a physical, in a very physical way, right?

A positive memory: it exists in your head, but it will have a physical, you know, an observable emotional reaction that if you think of this from a measurement standpoint, you can measure certain neurotransmitters being released into your bloodstream, for example. And so it may not be tangible in the sense of being able to see it. But we know it's there. We know it's real.

If you can get people to interact with the environment that they're operating in, and there's some level of motivation to be a part of that process and be a part of that group as a social phenomenon, I think what happens is people become embedded in these communities, If you will. And because of that there's a link that gets created. There's a bond, there's an emotional component, not just the act of doing something. So it's not just a behavior in a vacuum. There's this—there's a social component.

But by and large, there's an acceptance because you're part of the group. And by doing that, people become comfortable. It's within their comfort zone. And depending on the type of personality you are, this can really hook people in and not in any kind of dysfunctional way. In a very functional way; it can serve to provide a sense of security for people, even.

Alex: Wow. Security. I never thought of something like Neopets or RuneScape or LiveJournal as a source of security. But does that just mean everyone is a sucker for something consistent because it feels like an emotionally ‘safe’ choice?

Debb: Yeah, so this is a really interesting point. So people, on some level, people like consistency and routine and predictability. On the other hand, people also like things that are new and different.

Alex: From Debb’s perspective, the appeal of these sites, and the personalities they attract, actually split two ways. One is for people who do like things that feel familiar, and one is for people who feel something new, even though they’ve experienced that thing before.

Debb: On one hand, if something is repetitively done, it seems on the outside looking in as though it's the same thing over and over, but there's some research that suggests that for the person doing it, the end user, so to speak, it's actually a different experience, right?

You're not doing the same thing over and over again. You're actually picking up new things when you repeat it, when you do it again, ultimately contributing to that overall sense of mastery. It's just like people who like to watch the same old movie a hundred times. Every time you watch it, you're watching it in a sense from a new set of eyes.

Alex: So that might answer one question: what makes people stay. But it begs another… what makes people start? You can probably assume that certain personality types might be more likely to start something new than others—mostly because there’s a lot of friction to establish yourself in a community early on.

Debb: Maybe the curse and the beauty of, of cyberspace is that we can, you know, the presence that we have online, It could be the same as our offline selves, but it can also be very different. They can highlight different pieces of who we are. And so sometimes, if someone is very introverted in everyday life, they might find an outlet in an online forum or a, you know,a gaming forum or, or, you know, kind of a multiplayer game online, they might be able to be that extroverted person that in the day-to-day physical world, they just can't, they can't do it.

Maybe they have social anxiety or something like that, or they're just shy and reserved, but online it's an opportunity. So you combine, let's say someone who is, you know, maybe a little bit open to some new experiences, but also somewhat of an introvert. That may not work in kind of, you know, day-to-day life.

And this provides them with that outlet to be, you know, this other versus this other portion of themselves. It's not so much that they're becoming a different person in online versus offline worlds. It's that who they are all different aspects of who they are are, are showing up. Just like when you, you know, when you're hanging out with your friends, you act very differently than when you're hanging out with your parents.

And so some of these online communities that have persisted for a long time, they represent the opportunity to be outgoing in a certain way, for example, that maybe inday-to-day life, they, they can't find. And so that continually draws people back.

When we look—when you’re considering why people come back to some of these communities after long breaks, one of the things to keep in the first thing to keep in mind is that a lot of, a lot of individuals feel that sense of community. And just because you leave doesn't mean your identity with that community is lost.

Just as an example, I was, I was looking at some of the Gaia web forums. One person in one of these forums asked the question, do people still play Gaia Online?

And one of the responses that I found that I thought was really insightful, it was straightforward, but very insightful. The person responded saying “you don't play Gaia. It's not a game. It's a social network with avatar based form representation and there's games on the site. But the site itself isn't the game. That's why most of us are still here. It's a community. We have friends here.”

That seems perfect as a comprehensive response, why people come back: it's because they're connected to that. There is a piece of their identity that's associated with it. It becomes just part of who you are, so you never feel like an outsider.

Alex: Identity… now that is a word we keep hearing. People don’t just passively consume the content on these sites for 20 years. Rather they feel represented by these sites. And creating that identity in the first place is as much a conversation that happens in your own head as it is a conversation you have with a community.

Harley: So there's this whole idea that people investigate spaces online, particularly on online communities, where they feel like they can be themselves, where they can be authentic. And that kind of stays with, with us over time.

Alex: This voice belongs to Dave Harley, a principal lecturer from Brighton University and an expert on cyberpsychology. And he made an argument that stopped me in my tracks.

Harley: I think it's fair to say that all online communities do, they do work in ways that one would never anticipate. And I think probably people do gravitate towards those spaces which manage to maintain a certain form of the internet—you know, perhaps a more, a slower, more deliberate way of interacting. I mean, this is difficult to completely research, but that’s some of the sense that I get.

And what's interesting is that some of those spaces—it's really important. To be able to reflect upon who you are, so that the deliberations about how you present yourself are really important. And the way in which social media in particular has shifted over time is that it's become less deliberate in that way. There's less of the kind of, perhaps, text-based, having time to think about your responses—if you're creating a character in an online game, having time to kind of choose what outfit you're going to wear or how you're going to present yourself. Those sort of deliberations are really important for kind of feeling authentic.

And what you see with social media—and I wonder whether there's a contrast here, is that social media tends to be—it tends to be slightly more unconscious. It kind of hijacks some of those unconscious social reflexes that mean that we are always engaged, but we're not necessarily creating or curating ourselves in the same way.

Alex: This is something I didn’t even think of, but makes complete sense. Being deliberate early on makes something more appealing. These older sites tend to build in ways for people to represent their identity in a deliberate way. It makes sense that the more investment you place in developing that identity, the more likely you’ll create an emotional attachment to it. Just think of how powerful an exercise this is for all of us who played these games and spent hundreds of hours on these forums and sites when we were kids—when we were still trying to figure out what our identity even was in the first place.

Harley: I mean, even when you think about Second Life, it has continued to be a real place where people go back and maintain relationships. You know, it's, it's been a fascinating place to study the way human relationships have evolved through that whole kind of virtual world.

I would imagine that there are probably a couple of routes that people take when they kind of get completely immersed in a kind of online space. So some of the studies I've done on YouTube, for instance, I know that little communities emerge. And what happens is that those relationships transcend the kind of online scenario. So they become, if you like, an old-style community—people meet, they have emotional connection. And that is ongoing.

You know, once you have an actual relationship with someone that you've met in real life, it takes on a different category, if you like, a different significance. And then I think there's something about the kind of old-style internet, where there was a form of anonymity where you possibly never expected to meet that person, but your familiarity with them grows through your interactions online, and that becomes a place where you come to express yourself in new ways, and that has a kind of value that’s difficult to deny.

When we talk about anonymity online, I think it's very easy to take it as a kind of all or nothing, but of course It's a journey, isn't it? When you encounter someone else online, you can be completely anonymous. And in different spaces at different times, you will disclose aspects of yourself and you’ll be more willing to disclose aspects of yourself.

And we know that in certain spaces, the willingness to disclose everything about yourself, it's really kind of accelerated. It's difficult to exactly say what anonymity means in a certain space, but it's certainly something that we work with in order to manage, like, our relationships with other people. Whether we feel safe enough to disclose certain things, whether we feel safe enough to express certain aspects of ourselves... are related to how anonymous we feel, how safe we feel.

Alex: That’s another variable I overlooked when researching these never-ending websites—the psychology of disclosure. When people are open enough to disclose something about themselves— like how they look, how they want to look, how they feel about this or that—well, that retro website gets pulled out of the past. It’s now a part of your modern community, because not only did it evolve alongside you, but your profile reflects your modern values and ideas.

And suddenly, you have this domino effect of psychology. You have people who feel like they’ve contributed to shaping a space, which inevitably means you have people who start to feel accountable for how they shape the space.

One of the most fascinating practices I heard repeated time and again was that in the online game of RuneScape, veteran players felt the urge to shepherd new players who needed directions and advice. It becomes even more obvious how these sites hit close to home when you consider that many of us spent time on these sites at transitional points in our lives—whether that be during a pandemic or as angsty teens trying to figure out who we were.

Harley: Yeah. I mean, I think, I think it does come back to the, kind of, being able to express aspects of yourself that you can't express anywhere else. And, and although in studies, you know, they've kind of looked at this as a sort of transitional space. So the idea that, you know, life, if you get spaces where someone's coming out, you know, that they're kind of declaring to the world their gayness or whatever, that might be a space where they start off being able to be themselves in that particular way, but isn't necessarily where they have to reside.

Alex: And if you don’t have to reside somewhere, that means you can straddle multiple identities, experiment with who you want to become, and feel a sense of home in even virtual, non-physical spaces.

Harley: The research that I do, I very much think about online communities as cultures. At the same time as we might be discovering something about ourselves, we're also taking part in a culture that is unique.

And so of course, if, if you say you've grown up in, I don't know, Spain or something. Okay. And you've left Spain because… whatever happens, you go to university or you, you, kind of, get a job or whatever, there will still be a part of you that is Spanish. So when you return to Spain, that part of you comes alive again.

And I think that's true of particular games, particularly nostalgic games, which might spark memories of a certain time of your life, of a certain way of being, if you like, and it will bring that back to you in a very lived way, rather than it being a, kind of, just a thought.

I think that there's a certain element of, of coming to terms with the way in which technology pushes you along, it kind of transforms your experience and maybe it's, it's returning to those earlier incarnations of the internet or wherever the game is that made you appreciate how things have changed in that time.

And I think so much of both the kind of technological, digital revolution feels out of our control. It's like an inevitable progress that we cannot deny. I think going back to kind of nostalgic forms of technology gives us some kind of, I don't know what you call it, like, it reminds you that it's a choice you're making, that you can go back and use those old technologies and actually they're as much fun and they engage you as much as these kinds of newfangled, innate, like… everything is kind of on your phone, immediate, realistic, et cetera. But there's value in, in kind of old technology and appreciating that. I think it’s definitely a reminder of that in some ways.

Alex: And while old and new technology both have their pros, there’s a real, almost subversive pressure placed on us with the pacing of new technology…

Harley: Yeah. I think perhaps that this is another way in which technology and social media in particular pushes us to, to accept it, is that it presents us with novelty. So it's, it's one of the ways in which we are kind of caught by the kind of technological progress. And, and we find it difficult at times to kind of take a step back and be deliberate and be reflective.

And I think that there's something about the way it changes your mindset when you go back to a, like an old game, which is all pixelated and, and what you have to do is so obvious that, you know, if you had a modern mindset, you’d say, “Oh, that's boring,” but actually in another mindset, it's like, well, actually this is something that I enjoy, and this is something I can choose to go a bit slower, to… being more deliberate. And this is a very small kind of rejection of, of, you know, the new, the modern, the constantly changing, so I think that is true. Yeah.

And it does make me wonder, you know… This is all heading in a sense of… what do people want from the internet? And I think that there's also a possibility to kind of return to some of those kind of reflective, more deliberate ways of using the internet, where you can connect with, with people across, across the globe with a healthy kind of anonymity, you know, where you're sharing something about your humanity. So I—I'm interested to see where this goes, because I think some of these things that make nostalgia important for people are still important, you know? That’s why people go back to them.

Alex: For the record, nostalgia isn't just for the people who experienced a thing. You can be nostalgic for things you were never even alive for. Kind of like how I have nostalgia for the Beatles and the ‘60s, but I was born in the ‘90s. I have no reason to be nostalgic for that era, but I am. Nostalgia can be intergenerational.

But sometimes, generations clash. So much so they split communities right down the middle- just like we see with RuneScape. I interviewed Sage , a player who’s been involved for 15 years since 2006, and a paying member for nearly as long.

Sage: So when RuneScape was originally released, it was a very bare-bones RPG. Uh, that was very much click and wait more closer to something like AdventureQuest, if that, if that rings any bells, uh, than something like World of Warcraft. Um, at a certain point, they switched over to a more ability-based combat system. And that was a huge change from, like, the paradigm of like, pretty much basic combat peaking, and a lot of people, including myself, quit during that time for a long time.

Alex: That sounds kind of familiar right? Like Jaye and Neopets: Frustration and disappointment with how the game tried to change.

I had to see some of this change for myself, so in researching for this podcast, I went back and played the game. To my absolute shock these characters, while still pretty retro looking, had actual faces! I considered this a HUGE upgrade from what I remember- characters with pixels the size of your fist.

Sage: Yep, I remember—I remember when that got added, when, when faces got added to players and that was huge. Because before that it was just kind of probably like two dots and like a line for, for a mouth.

And then as far as the nostalgia factor, two versions of the game currently exist. There's RuneScape, sometimes referred to as RS3, which has all of the changes over the past many years. and then there's OSRS or Old-School RuneScape, which is essentially a snapshot pulled from I think, 2012. And that has that more nostalgia factor. And both games are highly popular. And I think the Old-School RuneScape really captures that nostalgia more than RS3.

Alex: Sage is right. RuneScape is actually kind of an odd and fascinating case study—because, even though the community split, it’s the opposite of dying. It’s actually doing the best it’s ever done. Which is objectively weird.

Because when you look at the Google Trend data, interest for RuneScape peaked in 2013, and pretty consistently declined the past 10 or so years. So you would expect that no one would be playing anymore. But if you look at the number of users on the site now, the original version has steadily and consistently grown in popularity, peaking in—you guessed it—2020.

In fact, the game hit a record number of paying subscribers in 2019, clocking in at 1.1 million members. That’s in addition to the mobile version of the game hitting 8 million installs.

Sage: So RuneScape is very diverse. You can pretty much do almost anything that you want. It's not like other games, like, let's say World of Warcraft, where you're locked into a certain play style based off of what character you play. You don't play as a role. You don't play as a class. You can max every skill, max no skills. You can just quest, just kill things. And that's your choice.

Alex: Sounds just like what Debb said… Autonomy with the opportunity for competency. But what about relatedness?

Sage: I've been in my clan for... seven or eight years at this point. And if it wasn't for that community, I probably wouldn't still be playing the game. ‘Cause I definitely, like—even when I'm on a break, I'll stop by my clan’s Discord, say hi. I'm in Snapchat groups with them in real life. So I have interaction with them outside of the game that has value other than just purely in game.

Alex: That relatedness worked for Sage, both as a kid, and now as an adult.

Sage: I think a lot of kids played RuneScape. Uh, either they, a lot of people discovered it through Miniclip, and it was the type of game that people went to school the next day to talk about like, “Oh, what did you do last night?”

And it was kind of the, during the, like the Wild West of video games, in combination with being really young.

So in, in the current—yeah, of Runescape, there's an efficiency… mindscape, mentality. Where, if you are doing something, you want to do it—you want to do it the most efficient way, because as adults that are still playing this game, our time is limited. Our resources are limited. So a lot of people want to get from point A to point B as fast as possible, instead of just, kind of, meandering around and smelling the roses, so to speak.

Alex: Now that’s a great phrase. Smelling the roses. Because I think, based on all these interviews, that’s why these sites have been able to hang on. They don’t demand attention. They can even just be on in the background, but they’re always there. Enough that they become an institution to our daily routine- for better or worse.

Sage: That's the best thing about RuneScape, is it's a game that you can play in the background. You can be playing RuneScape, doing homework and watching TV all at the same time. So that's where a lot of those hours stack up for a lot of people. And so I'd say now as like a full-time student, full-time employee, as well as a full-time RuneScape player, I probably play, I don't even know how many hours a week. It’s probably a scary amount.

There's definitely, there's definitely a nostalgia that brings people back. I don't know if it's really nostalgia for me, ‘cause it's a very different game than it used to be. Um, I like to call RuneScape a “sunk cost fallacy,” because so many people that play the game may not even actively enjoy playing it. They just keep playing it because they've played it for so long that it would be a waste of time if they stopped now. And, and the game is really well-designed to, to keep people in that loop, like, whether intentionally or accidentally. There's mechanics that make you not want to miss out on something that might be a limited time event, whether that's holiday events or just the new cosmetic that might be only available this month.

I'm definitely going to say I sometimes hate-play the game, and I'd say most of the player base at some point in their time playing hate-plays the game, because, like, at this point in the game, I'm—I'm maxed. I have all like the money and levels that I could ever really need. So I'm to the point where I can kind of slow down and enjoy content.

Alex: Since a lot of these sites struggle to balance updating for modern styles versus keeping the retro feel their fans adore, the content can be a surprisingly jarring experience. A lot like what Jaye talked about when she felt those pangs of disappointment with Neopets.

When you think about it. It’s kind of funny. It’s like the actual environment of the game mirrors the environments in the minds of a player. Half of it is familiar and comforting, and half of it is clouded by conflict. things are moving forward and updating, ostensibly so they can work better; but it's not the original.

I think it’s worth emphasizing right here, that, while a lot of people told us that this energy would get redirected to other games or back into real life, that doesn’t mean their investment into this game didn’t yield any rewards for them. More often than not, it actually helped shape the person they became.

Sage: I was always into math as a kid and throughout high school and then economics in high school made me see, like, “Hey, I kinda like this.” And I was probably around, uh, around the time where, like I might've been playing RuneScape during that period. And then the way trading works on the exchange and then into my time at community college and probably playing RuneScape during that time. And—as well as trading on the stock market, which I've probably been doing for like, almost as long as I've been playing RuneScape.

A lot of the things— like, I type fast because I played RuneScape as a kid, you used to have to type what you want, what you wanted to—like, I'm like trying to buy, I'm trying to sell. So you—a lot of people got their typing skills from RuneScape, myself definitely included. And there's all sorts of just little pieces of knowledge that, like, I know as an adult, because I played RuneScape as a kid.

I think I mentioned using RuneScape and video games as a coping mechanism earlier, but it's not—it's definitely true for a lot of people. I know people that come to RuneScape that may not even participate in that much of the content. They just might get on RuneScape to go fishing.

Uh, it's, it's a, it's a joke inside of the RuneScape community that you don't quit RuneScape. You just go AFK.

Alex: Just AFK: “away from keyboard.” Just for a little bit...

These players, on countless sites—RuneScape, Neopets, Myspace, Gaia Online, you name it—they love these sites so much, that they play for decades, often on multiple accounts, through thick and thin, through breaking homepages, hacks, companies straight up corrupting account data and losing player progress—through it all.

That’s because, despite everything, it’s still worth it. These players deliberately developed identities... disclosed parts of themselves to communities that stuck through itwith them… they found ways to be accountable to each other... have autonomy and feel like they’ve achieved mastery in the stories of their own lives: online and offline.

If anything, I walked into this story with a bad assumption: that these players were stuck in time, stuck wanting to relive a part of their lives like a broken record. But what these interviews have proven is that they do anything but that. Consistency is just one part of the greater value of these sites, and these sites don’t hold these players back. If anything, it’s the piece of who they are that helps them move forward through the uncertainty of the future.

This has been Case By Case, produced by myself, Alex Cardinale, and my fellow producer, Kate Redding. Thank you so much to Professors Harley and Debb, and our player interviews—Jaye, Sage, Felipe, Sara and David. You can learn more about the experts and players we interviewed in the show notes.

If you’d like to read more of the pitches we publish for journalists every week, you can find us at casebycase.substack.com. Make sure to rate and review on whatever app you’re listening on, as it helps us grow this resource for more journalists every day.

Thank you so much for listening. More podcasts to come.

We’ll see you on the wire.